If you’re like me, you probably thought the only thing people who don’t know where their next meal is coming from just needed access to food.

That is not wrong, but it’s not right, either.

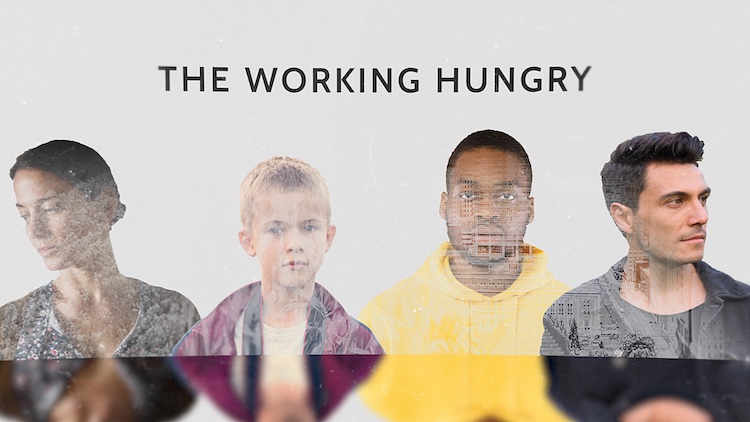

A recent showing of The Working Hungry, written and produced by my friend Shannon Cagle Dawson, enlightened me. The 30-minute, Emmy-nominated documentary was shown April 26 atKan-Kan Cinema and Brasserie (a very cool place, BTW).

What I learned

Access to food is critical to the health and welfare of everyone. We all know that. However, the working poor – those folks who work two or three jobs to put food on their tables, pay rent and utilities, need more than food.

They need a living wage. They are the working hungry. Until people have a living wage, they are never able to get ahead. Many are one stolen bicycle away from losing a job because they have no transportation. Or they need to stay home with a sick child, putting their job at risk because there are no sick days.

The documentary focuses on three Hoosiers in various states of work, housing and food distribution. Lamont Hollins, a Brownsburg chef, developed a family business, cooking and selling barbecue as a caterer. Carolyn Begley is a longtime volunteer at Good Samaritan Food Pantry in North Vernon. She talked about the overwhelming number of people who converge on the pantry when it is open. Robert Miles, a veteran of wars in Bosnia and Afghanistan, who finally landed a job at the VA hospital in Indianapolis after many tries.

Startling stats

The acronym ALICE describes this group – Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. These are families who can’t afford housing, childcare, food, transportation, healthcare and technology, but who work every day. These are the people who prepare and serve our food at fast-food restaurants; who clean offices and hotel rooms; work in childcare; provide homecare for our sick, elderly or disabled relatives.

At least 800,000 Hoosiers are food insecure and about 15 percent of them are children. That’s 120,000 kids who don’t know where their next meal is coming from, even though their parents work.

Twelve of the 20 most common positions don’t pay a living wage. That’s 700,000 jobs. A living wage in Indiana is $18 an hour, plus health insurance, said the panel of experts at the showing, including Jeanette Jones, human resources director at Mays Chemical Co. in Indianapolis. Mays participates in EmployIndy, companies that pledge to pay their workers a living wage and provide health insurance. About 70 Marion County companies have signed on. EmployIndy also connects people looking for jobs with potential employers.

Challenges beyond food and work

Applying for housing is an arduous affair, said Miles. Having a job is great, he said, but he’d also like to have a place where his family could live. In the documentary, they are holed up in a motel in Hamilton County.

The paperwork to get housing can be overwhelming for people who have lost documents because they’ve had to move a lot or lived in their vehicle. Not having a former address is a problem. Applying for housing means you need access to a computer. Applying for housing frequently requires a fee. The fee eats into a family’s resources, and it means you need electronic access to funds. “Everything is online,” the veteran said.

What can gardeners do?

- Donate fresh produce to food pantries, food kitchens or similar organizations.

- When we hire individual to work in our landscape, pay them a reasonable wage. If we hire a landscaping company, ask about wages and health insurance for workers.

- Arrange to have a viewing of the documentary for your garden club, Master Gardener group, neighborhood association, business lunch and learn. Or stream it online.